“Quiet people have the loudest minds.” Stephen Hawking.

Thousands of nonspeakers around the world are spelling fluently on letterboards and keyboards. They are graduating from regular high schools and colleges. They have had their lives and dreams returned to them. And yet millions remain underestimated and misunderstood. It’s time to start listening.

These are, respectively, the opening and closing title cards of the new movie Spellers, a pro-FC documentary directed by Pat R. Notaro, III and based loosely on J.B. Handley’s Underestimated: An Autism Miracle. (See our review here). The movie’s trailer also includes this quote:

There’s never any doubt in my mind when someone walks into my room that they can and will spell for me. That they can and do want to learn.

The underlying message: all non-speakers have the capacity to spell out sophisticated messages.

Spellers showcases nine individuals, including Handley’s son, who purportedly do just this—thanks to a variant of FC known as Spelling to Communicate (S2C). The movie refers to these individuals as “spellers,” and, for convenience, I’ll do the same. But while the term generally implies conscious spelling by the person who appears to be selecting the letters, I will be making no such assumptions here.

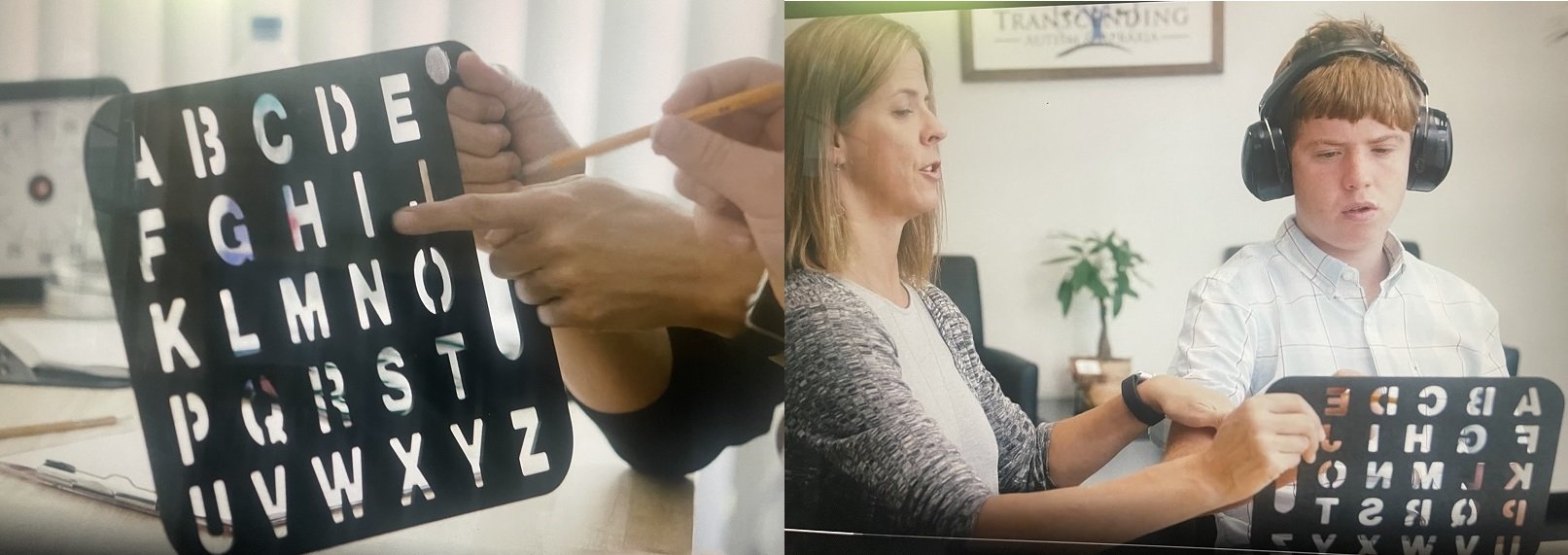

Mostly I’ll be focusing on the speller’s typing sessions. Typing in S2C involves either a held-up stencil board (or boards) through which the speller pokes a pencil (the initial stages of S2C), or a held-up letterboard (the next stage), or a held-up keyboard, or (the final stage) a stationary keyboard. Another key ingredient of S2C, as with all forms of FC, is a facilitator. (S2C practitioners use the term “communication partner”). This person sits or stands next to the speller, holds up the letterboard and, even in the final stage, prompts the speller through voice and gesture.

In reviewing these sessions, I’ll look at ways in which the facilitators—unwittingly or not—guide the messages attributed to the spellers. I’ll then explore additional clues that betray who’s actually in control. Finally, I’ll look at some characteristics of the spelled-out messages and at some of the underlying contradictions of the broader belief system that encircles S2C.

But I’ll begin my review with the talking heads: the self-styled experts in the field, namely Elizabeth Vosseller and Dara Johnson. Vosseller is a speech-language pathologist who is hailed by her acolytes as the “founder of S2C.” She’s also the source of both the third quote above (“There’s never been any doubt…”) and of the five misleading claims below, which I’ve interleaved with my corrections:

Claim 1: “What we do is we take the movement out of the fine motor of the digits and put it in gross motor of the arm.”

Correction 1: Pointing to letters on a letterboard is a fine motor skill.

Claim 2: “Speech is 100% motor, language is 100 cognitive. And you can tell they’re in two different areas of the brain. Speech up here, language is down there.”

Correction 2: Language is not 100% cognitive: one can have cognitive disabilities without language disabilities. That’s one reason why IQ tests have verbal and nonverbal subtests. There is, furthermore, no “up here” vs. “down there” separation of speech from language. Speech involves not just the motor cortex, but also a brain region called Broca’s area. Broca’s area is involved in other aspects of language, including the production of written language and sign language.

Claim 3: “All tests of.. language, cognition, academics, IQ require motor. Every single one. So you either have to speak it or do it. You know, put the thing in the thing. Touch this. Touch that. Give me the this. Give me the that. But we never teach the motor. We do not teach the motor.”

Correction 3: Most cognitive assessments do not require motor skills that are lacking in autism. The most likely reason for failing to point, touch, or give during cognitive assessments are problems with comprehension. “Teaching the motor” would not solve this problem.

Claim 4: If a child points to letters at the wrong end of the letterboard, it’s because “there’s a really strong draw to go to that left side of board because he’s been taught all life to start left, go right.”

Correction 4: “Start left, go right” applies to sheets of paper, not to letterboards and keyboards. It does not cause keyboard users to ignore the keyboard’s letter labels and select letters on the left when they intend to select letters on the right. Nor does it cause piano players to mistakenly select low notes before high notes when playing songs. The most likely reason a person selects the wrong letter is that they don’t know which letter is correct.

Moving on to Dara Johnson, PhD, she is an occupational therapist who founded Spellers Center Tampa and the Invictus Academy, a school that uses S2C. The film adds one more credential: Johnson is the co-founder of something called the “Spellers Revolution.” Here’s her claim and my correction:

Claim 5: “The early research was on autism as a cognitive disability… The assumption that individuals right from the get-go who have autism also have a cognitive disability is completely inaccurate. And the reason is because of what’s called apraxia. And apraxia is an inability to perform on demand a specific movement even though it is fully understood. Traditional assessments, neurological testing, academic testing, all focus on pointing, writing, or speaking which all are motor skills.”

Correction 5: Research continues to show that autism is a cognitive disability: specifically a socio-cognitive disability. Some autistic individuals also have a general cognitive disability. On cognitive testing and on what’s involved in language, see above.

Finally, I’d like to address a claim made by Ginnie Breen, the mother of a speller and the chairman of Communication4All:

Claim 6: “Provisions in Title 2 of the ADA say that people with communication disorders have the right to equal communication of their choosing in schools.”

Correction 6: As far as communication goes, what Title 2 of the ADA actually says is this: “The ADA requires state/local governments to communicate as effectively with people with disabilities as with others.” For effective communication with deaf people, for example, they suggest sign language interpreters.

Now let’s turn to the spelling sessions and the ways in which the facilitators—unwittingly or not—guide the messages attributed to the spellers. In the dozen or so S2C sessions showcased in Spellers, we see the facilitators exerting control in the following ways:

1. Board movements: In all sessions in which the facilitator holds up the letterboard or keyboard, the board is never stationary. Generally, it moves in directions that shorten the distance between the speller’s extended index finger or pencil and whichever letter is subsequently deemed to have been selected. Many of these movements are relatively small and therefore are only part of how facilitators control letter selection. But there’s one major exception: when the facilitator decides to “reset” the board. Resetting involves whisking the letterboard away from the speller and then thrusting it back. This typically happens when the speller is deemed to have lost focus, or (more insidiously) has chosen, or is about to choose, the wrong letter. When the facilitator thrusts the board back, it’s often to a location that brings the targeted letter closer to the speller’s finger or pencil than it was before the reset. Finally, facilitators can whisk away the letterboard once and for all in order to end a message—and often they do this without appearing to check in with the spellers to see if they’re actually done spelling.

2. Vocal and gestural cues: Throughout most of the S2C sessions, we hear a variety of phrases come out of the mouths of the facilitators. Different phrases co-occur with different speller behaviors. We hear:

“Keep going” and/or “Go, go, go” when the speller is moving towards the correct letter.

“Go for it,” “You got this,” or “Get it, get it, get it,” “Which one g or b?” or “Pick whichever one you want” when the speller is close to the correct letter.

“Get it,” “Yeah,” or “Mm-hmm” when the speller has reached the correct letter but hasn’t yet selected it.

“Mm-hmm,” “That makes sense,” “Real good,” or a reading back of the letter when the speller selects the correct letter.

“What makes sense?”, “Move your eyes,” “Get your eyes down,” “Open your eyes,” “Keep going,” “Hmm?”, “Oop,” “No, that doesn’t make sense,” or a repeating of the correct letters selected so far when the speller is about to select, or has selected, the wrong letter.

“Keep going,” “You’re good,” “Go ahead”, or “and...” when the speller still has letters left to go, particularly if he or she is getting restless or is perseverating on the current letter.

In addition, when the camera angle permits it, we sometimes see the facilitator’s free hand move in the direction that the speller’s hand needs to move in order to hit the correct letter.

3. Ignoring or dismissing incorrect letter selections

Across the various S2C sessions, we see numerous occasions where a letter that was clearly selected is ignored by the facilitator—not said out loud, and not incorporated into the facilitator’s transcription or pronunciation of the word or message.

In some cases, the facilitator makes an explicit correction (“i-o” doesn’t make sense”) or adjustment (“f-a-s-s? Oh: a-s-s-“)

In one case, after a speller selects t-e-b-a-c-h-e-r-s, the facilitator says “teachers?”, looks at the speller, and then, as if she’d obtained some sort of confirmation, nods her head and repeats “teachers”.

4. Interrupting the spelling. We’ve seen one way in which facilitators interrupt letter selection: whisking the letterboard away in order to “reset” it or terminate a message. The board may also be whisked away and replaced with one of three smaller boards that each display only a third of the alphabet. During one of the sessions, on three occasions when the speller’s selection was unclear or incorrect, the facilitator does just this. In addition to reducing by two-thirds the number of incorrect selections, this opens up additional opportunities for placing the target letter closer to the speller’s finger or pencil. Another tactic is simply to intercept the finger or pencil—something that Dawnmarie Gaivin, the facilitator for the majority of the movie’s S2C sessions, does several times. Interruptions that aren’t obviously motivated—e.g., by a loss of focus or a need for clarification—cry out for some sort of justification, and Gaivin obliges:

Twice when intercepting a speller’s hand and pencil (when there was no obvious problem with how he was holding it), she tells the speller to “hold the pencil like that.”

Once after whisking away the board and requisitioning the pencil, she sets the board down and uses the pencil to transcribe what the speller had spelled out earlier (omitting the nonsensical letter sequence that he had most recently selected). What may at first glance seem inconvenient (sharing a pencil with a speller) may actually prove convenient.

On two other occasions, she immediately follows the interruption by directing the speller to up look at her eyes (echoing a tactic used in evidence-based therapies, but whose application to S2C remains unclear).

Especially exemplary of much of this is the first of the S2C sessions, which starts about 4 minutes into the movie and involves a pencil and a stencil board. Here’s a breakdown of what happens after the speller is asked by Gaivin, who also facilitates, what he thinks of using the board:

With continuous prompts from Gaivin to “keep going” and “move your eyes”, the speller selects g-q-r-e.

Gaivin, ignoring the “q”, says “g-r-e, what makes sense?”

The speller selects “k”

Gaivin whisks away the board, says “look at me,” and points to her nose. Gaivin then resets the board.

The speller selects “a.”

Before he can select another letter, Gaivin puts down the board, takes his pencil, and transcribes “g-r-e-a”. She then resets the board and hands back his pencil.

The speller selects “t”.

Gaivin repeats back “great.”

With some pauses and oral prompts and board shifting, the speller selects l-i-f-e.

Gaivin repeats back “great life”.

Then the speller selects i-o-j

Gaivin, ignoring the “j”, repeats back “i-o… doesn’t make too much sense.” She takes away the pencil, puts down the board, and transcribes “great life.”

Gaivin then hands back the pencil, says “i”, resets the board, says “Start at i.”

The speller hesitates.

Gaivin points to “i” and repeats “start at i. So I know that”.

The speller follows her index finger to the “i”. He then selects “s.”

Gaivin immediately says “is”.

The speller then starts to point somewhere on the board with his pencil

Gaivin immediately whisks the board up and resets it.

The speller selects “g” and then another letter (the film cuts to a different camera and so we can’t see which one).

Gaivin immediately whisks away the board, tells him to “start at g” and briefly cups his fist.

The speller selects “g” twice and then “j”.

Gaivin shakes her head and says, “Make it make sense, g-j doesn’t make sense” and moves her free hand towards the middle of the board.

The speller points to “g” again and then hits “s.”

Gaivin takes his pencil, puts the board down and says, while ostensibly transcribing it, “Great life is.” She then resets the board and tries to give him back the pencil.

The speller is now looking down at his hands.

Gaivin says “Trust yourself—I love that. Great life is…”

The speller takes the pencil and pokes it towards the board.

Gaivin whisks up, points to her nose again, and says “Look at me for a sec… can you put your eyes up?” Then she resets the board.

The speller selects “a.”

Gaivin says, as if surprised at this new letter selection, “oh, a”.

With continuous vocal prompts from Gaivin, which crescendo as he approaches the final letter, the speller selects h-e-a-d.

Gaivin pronounces “Great life is ahead” while putting the board down.

The mother bursts into tears.

Consistent with facilitator control, there are a number of signs that the facilitators in Spellers, at least subconsciously, know what the messages are before they’re spelled out. For one thing, they behave as if they know when they’re about to end—e.g., by reassuring the speller that they’re “almost done”, or by setting aside the letterboard immediately after what they deem to be the final letter selection, without confirming this with the speller. How did Gaivin know that “great life is ahead” stopped there, instead of continuing, say, with the words “of me”, or “of me and I’m really looking forward to it”?

In addition, the facilitators sometimes display an extraordinary ability to hold long chunks of letters and incomplete phrases in their heads and then recite the entire message from memory once they consider it finished. For example, J.B. Handley, after extracting, bit by bit, the first half of a message (“I want to tell my future”, with “future” spelled f-u-t-t-r) somehow holds in his head the subsequent letter sequence, s-e-l-f-t-o-n-e-v-e-r-g-i-v-e-u-p-o-n-t-h-e-o-t-h-e-r-n-o-n-s-p-e-a-k-e-r-s, even while punctuating it here and there with “go ahead” and “and then.” As soon as he reaches that final “s”, Handley immediately and accurately reproduces the entire message: “I want to tell my future self never to give on other nonspeakers.”

Gaivin, accomplishing a similar mnemonic feat, suggests that she at least is aware of its potential implausibility. When she recites, from memory, “sensory stimuli assault my body constantly, brushes help me feel my hands,” she holds up the letterboard as if to suggest that she’s somehow reading the message off of the board.

Of course, it’s easier to reproduce a message that originated from your own mind rather than the mind of the person you’re facilitating.

As for the spellers, there are indications, not only that they aren’t the originators of the messages, but also that they aren’t even attending to the spelling process and often find it aversive. We see attempts to get up, or at least to cease spelling, smack in the middle of messages or, even, of words; we see one speller consistently look away from the board; we see spellers getting up as soon as facilitators put down the boards, completely uninterested in the effects their messages have on their audience. We see spellers stimming, fidgeting, pounding the table, and, in one case, even speaking while spelling. (Yes, some of these “non-speakers” can speak). Some of this speller’s words are probably echolalic (“I can see you”; “uh-oh try again”; “quiet”; “who is crying”), but others are clearly communicative (“I’m sad”, “I want Mama”), which raises two questions. How is this person able to switch back and forth between distinct messages, one spelled and others spoken? And why is she being forced to spell to communicate—especially since she bursts into tears and weeps extensively while spelling?

Initially, her facilitator (Gaivin again) interprets her distress as part and parcel of the message that was extracted from her: “Yeah, I’m going to guess that some of your emotions right now are because of that experience,” Gaivin adds: “You can tell me if that’s true or not. I could be projecting.” (We don’t see the speller get an opportunity to do that; the film instead cuts to her parents discussing what a hard time she had in school.) Later, we’re told that she “advocated to redo the interview”, and in the do-over, the extracted message downgrades the earlier spoken messages as “scripting”: “I was embarrassed by my scripting”. Who exactly was embarrassed, we might wonder.

Another source of wonder is the difficulty that many of the spellers display in locating specific letters on letterboards, even after months of practice. In one striking instance, while in the middle of spelling “all”, one person, having just selected the first “l”, moves his pencil away from the “l” and has to circle around again to relocate it. Proponents claim that S2C bypasses the motor challenges, so there must be some other culprit. What could it possibly be?

What about the wonder of messages slowly emerging from the fingers of non-speakers, serene music playing in the background, anxious parents waiting in suspense? In the context in which they unfold in Spellers, it’s easy to miss how many of these messages amount to bland promotions of S2C and of all that non-speakers can presumably achieve as a result of it:

Now I’m going to change the reality for myself and others.

I think knowing that we are intelligent and treating us with respect helps.

Teachers need to stop underestimating autistics; they need to start presuming up again and again.

I’d love to advocate for S2C in schools.

Following in their kids’ footsteps, many of the parents featured in Spellers now have practices that promote FC, some of which are mentioned in Spellers:

Dawnmarie Gaivin, a parent as well as a facilitator, is the founder of Spellers Center, San Diego.

Jennifer Larson is the founder of Holland Autism Center and Clinic and the CEO of the partner organization Holland Spellers.

Vaishnavy Sarathy, PhD runs a program focused on autism and nutrition that also promotes S2C.

Ginnie Breen, is the chairman of the board of the pro-FC organization Communication 4 All.

Thus, subtract away the mystique, and what Spellers amounts to is one giant infomercial for Spelling to Communicate.

One giant infomercial that’s filled with misinformation, misleading footage, and, finally, a few problematic convictions:

We hear parents lamenting the absence of reliable communication prior to their discovery of S2C. But Spellers shows numerous instances of reliable communication, some of it oral (“All done”; “I’m sad”) some of it gestural (those displays of distress and attempts to terminate the S2C sessions).

We hear some parents lament that science hasn’t caught up to S2C, seemingly unaware that S2C practitioners resist empirical testing. We hear others, including one self-professed scientist, state that they don’t care about the science. Finally, in what is perhaps the most revealing statement of all on this topic, one parent states “There should be academic literature focused strictly specifically on this area to help promote it”: an astonishing confusion of academics with advocacy.

One parent asks what people could possibly gain by perpetrating the hoax that FC skeptics claim that S2C is. Tragically, there’s plenty to gain, not the least of which are false hopes, even if there’s far more to lose.

Finally, there’s the issue of seeing vs. believing. On one hand, we’re not supposed to make assumptions about someone’s intelligence based on what we see when we observe them: as Vaishnavy Sarathy puts it, we should assume intelligence, “whether that intelligence is on display or not.” On the other hand, we are supposed to believe what we see when we watch the spellers spelling, because (assuming we don’t observe too closely) S2C can look pretty convincing. As J.B. Handley facilitates out of his son, “You just need to open your eyes.”

But perhaps the most problematic statement of all comes from S2C’s founder. When I quoted Vosseller in Claim 1 at the beginning of this review, I did not include the follow-up sentence. I conclude this review with the full quote:

What we do is we take the movement out of the fine motor of the digits and put it in gross motor of the arm. Because that’s so much easier to control.

Indeed it is. The question is who’s doing the controlling.