REFERENCES

Belmonte, M. K., Saxena-Chandhok, T., Cherian, R., Muneer, R., George, L., & Karanth, P. (2013). Oral motor deficits in speech-impaired children with autism. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience, 7, 47. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2013.00047

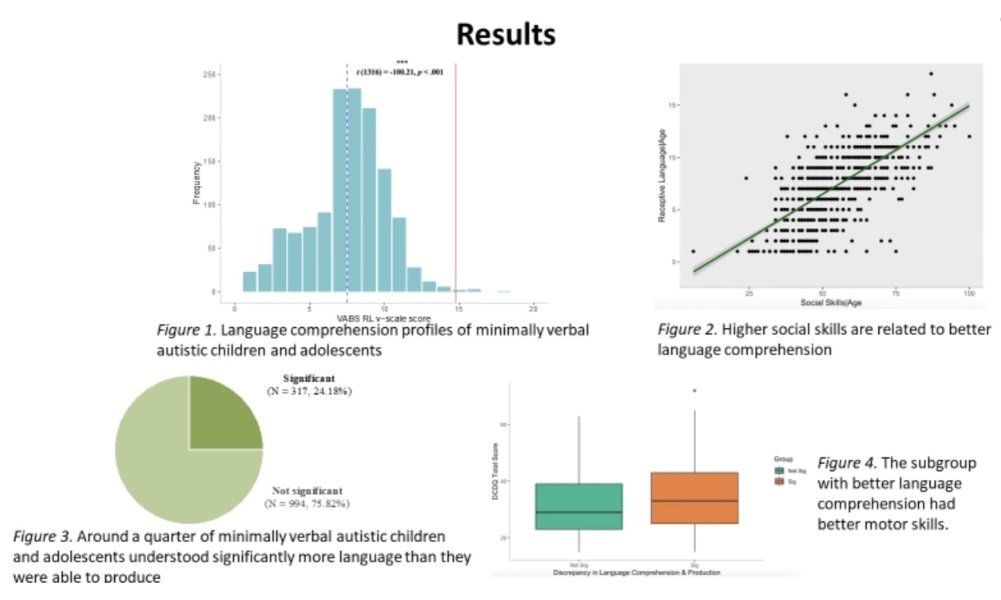

Chen, Y., Siles, B., Liberti, G., Tager-Flusberg, H. (2023). Discrepancies in Receptive and Expressive Language Profiles in Minimally Verbal Autistic Children. INSAR, 2023.

Chenausky, K., Brignell, A., Morgan, A., & Tager-Flusberg, H. (2019). Motor speech impairment predicts expressive language in minimally verbal, but not low verbal, individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Autism & developmental language impairments, 4, 10.1177/2396941519856333. https://doi.org/10.1177/2396941519856333

Haswell, C. C., Izawa, J., Dowell, L. R., Mostofsky, S. H., & Shadmehr, R. (2009). Representation of internal models of action in the autistic brain. Nature neuroscience, 12(8), 970–972. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2356

Karanth, P., Shaista, S., & Srikanth, N. (2010). Efficacy of communication DEALL--an indigenous early intervention program for children with autism spectrum disorders. Indian journal of pediatrics, 77(9), 957–962. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-010-0144-8

Kim, S. H., Paul, R., Tager-Flusberg, H., & Lord, C. (2014). Language and communication in autism. In F. Volkmar, R. Paul, S. J. Rogers, & K. A. Pelphrey (Eds.), Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders (4th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 232–363). Wiley.

https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118911389.hautc10McDaniel, J., Yoder, P., Woynaroski, T., & Watson, L. R. (2018). Predicting Receptive-Expressive Vocabulary Discrepancies in Preschool Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research : JSLHR, 61(6), 1426–1439. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_JSLHR-L-17-0101

Mody, M., Shui, A. M., Nowinski, L. A., Golas, S. B., Ferrone, C., O'Rourke, J. A., & McDougle, C. J. (2017). Communication Deficits and the Motor System: Exploring Patterns of Associations in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 47(1), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2934-y

Shriberg, L. D., Paul, R., Black, L. M., & van Santen, J. P. (2011). The hypothesis of apraxia of speech in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(4), 405–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1117-5 [4] Aside from words that label pictures, most written words cannot be learned in

Yoder, P., Watson, L. R., & Lambert, W. (2015). Value-added predictors of expressive and receptive language growth in initially nonverbal preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 45(5), 1254–1270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2286-4