(Cross-posted at FacilitatedCommunication.org.)

In this post, I return to one of the news stories I included in my FC news roundup from two weeks ago: a story on KQED’s California Report Magazine about a non-speaking 19-year-old who, after a breakthrough at age 16, defied impressions that, as reporter Sasha Khokha puts it, “he didn’t have the motor skills to point to the right answers in school.” The boy, who now goes by Jacob, was, purportedly, suddenly able to slowly type out full sentences with everything spelled correctly.

In one of the accompanying photographs, we can see Jacob engaging in the typical RPM/S2C-style of letter-selection, with someone else holding up a device to his extended index finger. We can also see a reference in the caption to a neurologist who “confirms that even though his father holds the device for him, Jacob types independently.” That neurologist, later identified as Dr. Margaret Bauman, has a history of defending FC, and it’s unclear on what basis she confirmed Jacob’s independence. In fact, the only way to establish independence is through a rigorous message-passing test in which the facilitator is reliably blinded. Bauman has been involved in only one published message-passing test, back in 1996. As we discuss here, that test was very far from rigorous.

Here comes the part I didn’t get to in my earlier post. According to the article, which is titled “Non-Verbal Teen to 'Take on the World' With a Symphony Written in His Head”:

Six months after learning to type, Jacob surprised his parents again. He told them he had a 70-minute symphony in his head… It’s called Unforgettable Sunrise.

Since Jacob can neither sing nor play an instrument (nor, apparently, read music), one of Jacob’s father’s collaborators, composer Rob Laufer, was brought in to translate Jacob’s verbal descriptions of the 6-movement, 70-minute symphony into a musical score on paper. Laufer, purportedly, “was amazed at the precision of Jacob’s vision for the symphony.”

But what, exactly, did it take for Laufer to translate Jacob’s vision onto paper? In the next dozen paragraphs I’m going to embark on what might seem like an off-topic excursion into symphonic composition and the translation of mental music into musical scores. But my objective here is to explore a broader question:

What is going on in the minds of parents and other facilitators when they assist minimally verbal individuals with nonverbal tasks and large projects that go beyond a few pages worth of typed output?

And my goal, once I emerge from this musical excursion towards the end of this post, is to formulate some possible answers that came to me only as I read and listened to this fascinating—if irresponsible—KQED report.

An excursion into classical music composition and translating mental music into notes on paper

People who attend classical music concerts regularly see multi-paragraph-long descriptions of the pieces being performed. Here’s an excerpt from the program notes of a recent Philadelphia Orchestra concert describing the first movement of Bruckner’s 4th symphony:

After a nocturnal string tremolo that opens the first movement (Bewegt, nicht zu schnell), the horn announces the sunrise and the dawn of a new day for hunting. The theme is eventually taken up by the rest of the orchestra and developed using Bruckner’s favorite rhythm of two beats followed by a triplet. A lighthearted second theme appears first in the strings, evoking the gentle folk-dance flavor that Mahler would later allude to in the Ländler movements of some of his symphonies. The main “horn call” motif then opens the development section, which ebbs and flows around a brief treatment of the second theme and further development of the “Bruckner rhythm,” culminating in a majestic brass chorale garlanded with string tremolos. This sets up the recapitulation, where the first theme is embroidered with an added flute solo, and the second theme is harmonically enriched with unusual modulations. An extended coda prepares for a triumphant return to E-flat at the conclusion.

—Luke Howard

Imagine, first, how long it would take someone extending an index finger to a held-up keyboard to type all this out.

Imagine, second, whether anyone reading this passage who had never heard Bruckner’s 4th symphony before, even if he is a skilled composer, could possibly translate it into the actual melodies, chords, rhythm, and orchestration of Bruckner’s 4th symphony. As pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim writes in a recent New York Times Op-Ed, “when we try to describe music with words, all we can do is articulate our reactions to it, and not grasp music itself.”

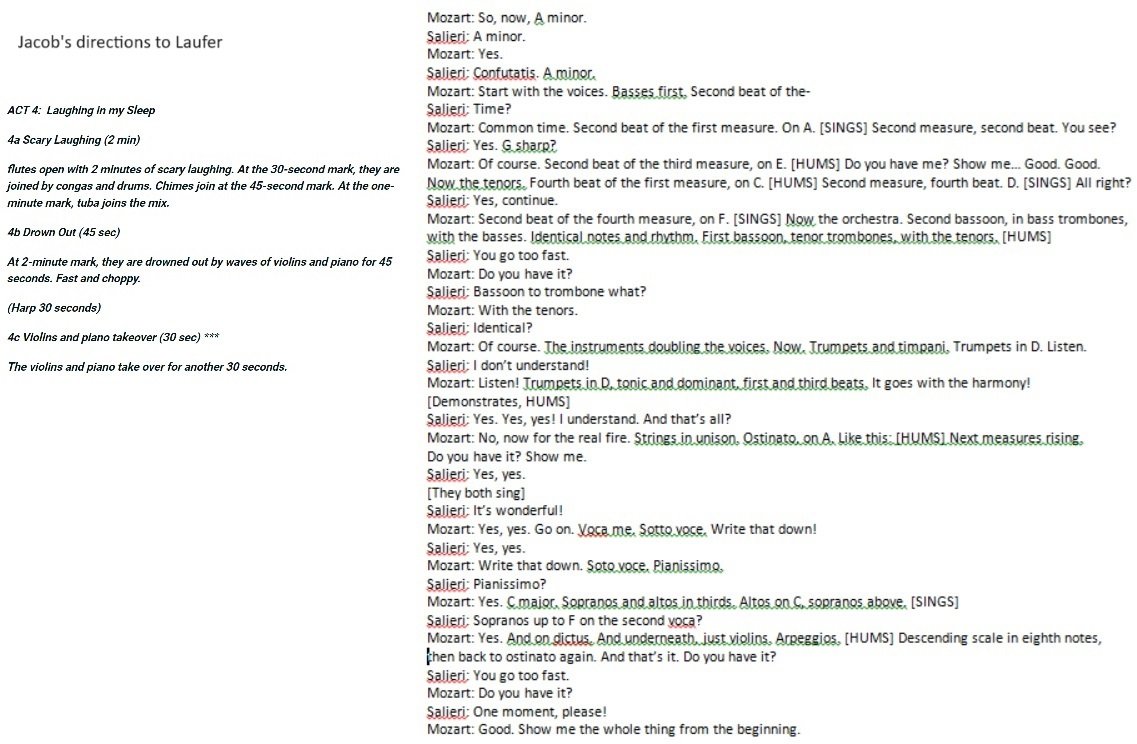

Perhaps a better way to grok what it takes for Person B to transcribe music from Person A’s head into notes on paper, with little other than Person A’s words to guide them, is to watch this scene from the movie Amadeus. Here Salieri sits at the foot of Mozart’s deathbed and attempts to transcribe, from Mozart’s verbal directions and humming, a short passage of the requiem that Mozart has inside his pillow-propped head. While this scene gives us some idea of what’s involved, though, even it strains credulity. Amadeus takes many liberties not just with Mozart’s life, but also with what Salieri can realistically glean from what comes out of Mozart’s mouth.

What’s crucial here, however, is that the Mozart character uses not just ordinary words, but musical terms, and, in addition, that he frequently illustrates melodies by humming them. Finally, since he can read music, he can check Salieri’s transcription. Here’s an excerpt from the scene:

Strings in unison. Ostinato, on A. Like this: [HUMS] Next measures rising. Do you have it? Show me.

In contrast, Jacob’s directions consist of words only: words about specific instruments, specific actions or emotions, and the number of iterations and/or for how long. For example:

It starts with piano bangs. Five bursts of cacophony.

In response to this particular prompt, Laufer had to guess the specific chords. He reports hypothesizing that Jacob might have in mind “this chord that I used to think about when I was young that I associated with the end of the world.” So Laufer played a specific chord he used to think about for Jacob, who apparently confirmed it as exactly what he had in mind—presumably by poking out some sort of affirmation on the keyboard held up by his father. In contrast to Mozart checking Salieri’s transcription, Jacob can only type “yes” or “no.“ But conveniently—because otherwise there could have been an endless back and forth—of all the tens of thousands of possible sets of five bangs within the 88 keys of the piano, Laufer guessed the correct ones.

Some of Jacob’s directions are more emotional:

I want triumph and happiness followed by terrified laughter and grief over so many years of painful silence.

Others more poetic:

The violins are demanding sleep and the horns are demanding pain. They battle for 3 minutes of call and response until the horns realize that they are defeated (Every manic horn met by soaring violin).

But while a skilled composer might translate these prompts into music that evokes them, countless translations are possible, and the chance of any particular one matching the music in someone else’s head is close to nil.

At this point, it might be interesting to contrast a sequence of prompts attributed to Jacob to a sequence of prompts attributed to Mozart in Amadeus.

It’s hard to imagine how Laufer could have translated a 70-minute symphony from thousands of prompts like the ones on the left unless most of the time he guessed correctly. But Laufer suggests this is more or less what happened: Jacob’s directions “made sense” because they were “coherent to the story he wanted to tell.”

Jacob, for his part, purportedly says:

I was unbelievably damn floored by Rob’s ability to tap into my emotions. I can only say that he is my great collaborator and he reads my musical mind. He can always feel what I want and turn it into amazing notes.

But there’s another possibility—assuming we take everything we read here on faith. Perhaps what was in Jacob’s head wasn’t really a symphony per se, but merely a bunch of verbal ideas for what kinds of emotions and interactions a symphony might express.

But that hardly counts as having an actual symphony in your head.

Regardless of what actually happened, there are a number of things at play here that suggest some broader possibilities about facilitation and translation in minimally verbal autism.

What might be going on in the minds of facilitators when they assist minimally verbal individuals with large projects and nonverbal tasks?

A number of facilitated individuals have accomplishments attributed to them that amount to far more than producing short passages of typed output. Many attend college and presumably produce long research papers, answer math problems, balance chemistry equations, and/or participate in labs; some direct movies; some compose; some co-author peer-reviewed journal articles. Even output that’s purely verbal must often go through multiple drafts, from large-scale reorganization to sentence- and paragraph-level revisions to word-level copy-edits to footnoting and formatting of bibliographies. Much of this goes beyond what can reasonably be accomplished by holding up keyboards to extended index fingers. So what happens behind closed doors?

Here’s a possibility. Perhaps, just like Laufer with Jacob, the facilitator goes beyond facilitation to “translation.” Perhaps the facilitator, like Laufer, makes very specific guesses at what their client wants to produce—without thinking too hard about how many actual possibilities are out there—and then seeks confirmation on the keyboard, and then finally (in cases where, unlike with Laufer and Jacob’s dad, the facilitator and translator are one and the same person) facilitates out affirmative responses from them. Perhaps the facilitator, like Laufer, presumes that the person is competent enough to produce something that “makes sense” and is “coherent,” and also that they know the person so well that they can guess what the person would produce on their own if they could: what kind of essay revision; what kind of movie direction; what kind of symphonic passage. And as long as they believe that they have obtained affirmation from their client on whether these are the melodies and chords, or the scene and camera angle, or the thesis statement and supporting paragraphs, or the steps in the mathematical solution or lab report, that their client had in mind, they can also believe that the resulting product is, in essence, the creation of their client.

As for the affirmation process, assuming the story of Jacob and the 70-minute symphony is representative, it seems to go swiftly: the facilitated answer to the suggested melodies and chords, or suggested scene and camera angle, or suggested thesis statement and sentence revisions, or suggested steps in the mathematical solution or lab report, is quite likely to be consistently “yes.”

In the majority of the cases where only a facilitator is involved (and not, say, a composer or cinematographer or mathematician), what all this means is that the facilitators may unwittingly produce not just verbal messages, but entire projects.

Anecdotally, we’ve heard anonymous behind-the-scenes accounts that precisely this sort of thing has happened: a facilitated college student has to write a long essay, the facilitator holds up the keyboard and extracts some starting words or sentences, the student wanders off after a while, and the facilitator writes the rest of the essay, checking in with the student later about whether it’s what she had in mind—or, worse, simply assuming that that’s what the student would have written, if only she could have.

Epilogue

Returning to the KQED piece, we learn that Jacob’s next composition is a Mozart-influenced opera. Will Laufer be up to the challenge? Time will tell

No comments:

Post a Comment