It has recently occurred to me that there may be a connection between:

- autism rates appearing to keep rising

- moderate autism appearing to be increasingly unusual relative to profound autism and mild autism

But before I get to that, I should probably defend the premise of the second question. "Moderate autism" means somewhat socially engaged and able to put words into phrases and sentences, but not fully fluent or grammatical. Moderate autism describes the two individuals with diagnosed autism in my extended family, but hardly anyone else I've encountered in person.

I first noticed the apparent rarity of moderate autism when I started reading autism memoirs. There are dozens of memoirs about kids who become fully fluent and socially engaged (Tony Attwood's "active but odd" Aspies). And there are dozens of memoirs of profound autism: kids who rarely engage socially and speak only a few isolated words and echoed phrases sometimes, if they speak at all.

In all my reading, I encountered only one memoir, Clara Park's The Siege, that described a child who was clearly--socially and linguistically--in the middle of the autism spectrum. Indeed, I was so excited to finally learn of someone who resembled my family members that I wrote the one and only fan letter I've ever written, became fast friends with the Park parents, and met Jessica Park several times in person.

Later, when I developed the SentenceWeaver, a program designed for autistic kids who are able to speak and read but have difficulty expressing themselves in fully grammatical sentences, I was once again confronted with the rarity of moderately autistic kids: the kids that seemed most likely to benefit from my work. And later still, when I went around the country interviewing autism parents and teachers on an NSF grant, it once again seemed as if everyone but me was dealing with either severe autism or what used to be called Asperger's Syndrome.

If this impression is correct, it's quite odd. It would suggest that autism doesn't involve a normal distribution from severe to mild:

But instead something like an inverse bell curve:

This sort of bimodal distribution, however, is not what you generally get with well-defined, empirically grounded categories. Such distributions suggest, instead, that we're dealing with two distinct phenomena. Indeed, a recent paper suggests that this may be the case: it suggests that higher functioning autism may have more in common with ADHD than with profound autism. That would place moderate autism either at the more severe end of some sort of HFA/ADHD spectrum, or at the higher end of some sort of "pure", ADHD-free autism spectrum.

But just the other day, I started suspecting that there might be a different explanation: a connection, that is, between the relative rarity of moderate autism and the rising rates of diagnosed autism--which in the US now stands at 1 in 36.

The perennial question is whether this increase is an increase in the rate of actual autism, or merely an increase in the rate at which autism is diagnosed. People who say there’s a real increase in autism tend to be clinicians who work in the field, who see their waiting lists getting longer and longer, and parents who are involved in autism parent groups, many of whom are on these waiting lists and/or send their kids to autism-specific programs. When you’re suddenly immersed in autism, it can seem like it’s suddenly everywhere--especially if you find yourself waiting for months for services because so many families are ahead of you in line.

If this increase is real, what is causing it? Most people no longer blame vaccines; those who still do seem to be a mostly fringe group that is also susceptible to other quack notions like chelation and facilitated communication (FC/RPM/S2C). But other theories abound. More older dads? More premature births? More toxins in the environment? More intermarriage between geeks?

Or is some or all of the increase simply an increase in autism identification and diagnosis, as opposed to actual autism incidence?

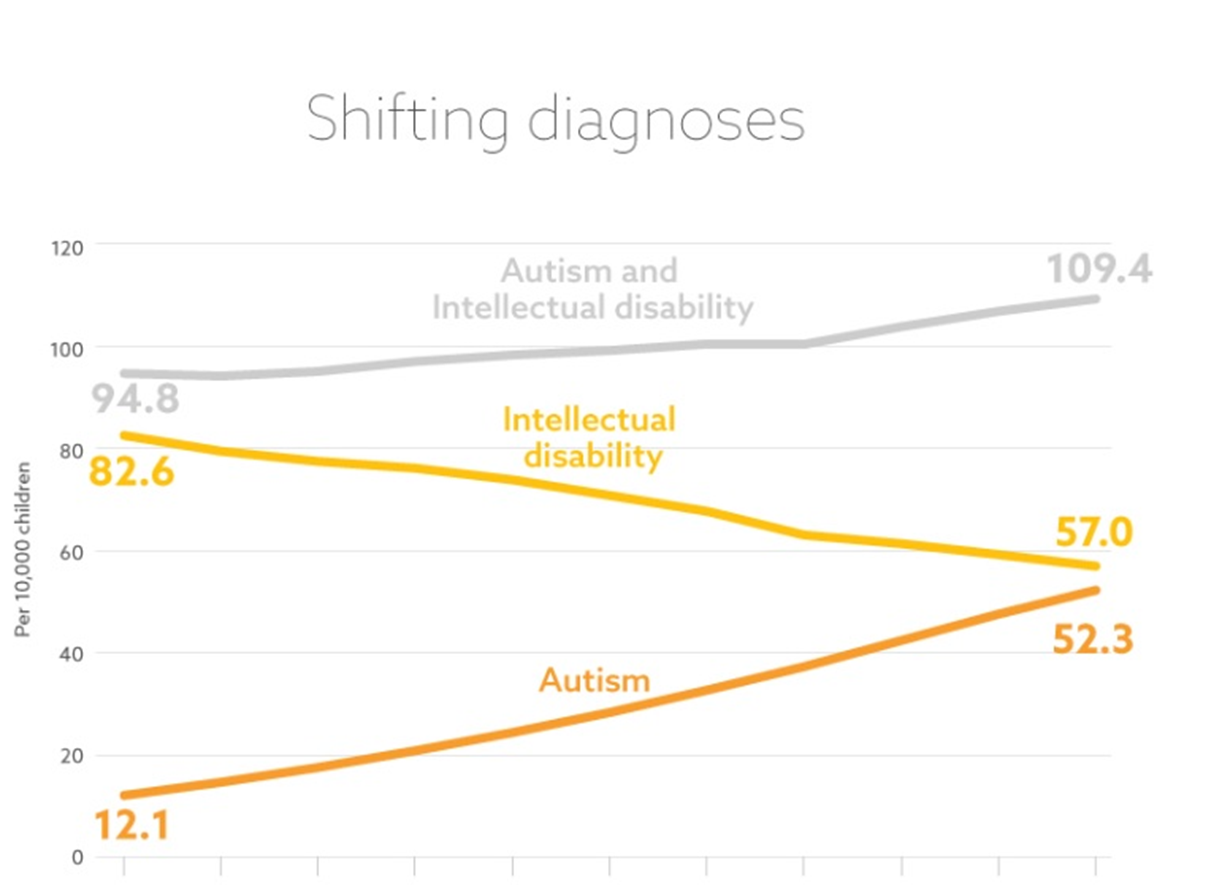

There are good reasons to think that changing patterns of identification and diagnosis are a major factor. The removal of the Asperger’s diagnosis from the DSM-5 in 2013 meant that people who would have been diagnosed with Asperger’s were instead diagnosed as autistic. Consistent with this is one study that observes that the increase in autism rates observed in individuals born in 1992 compared to individuals born in 2003 “is stronger for high than for low-functioning children.”

As for low-functioning autism, there's strong evidence that kids who used to be diagnosed as profoundly intellectually disabled are now being diagnosed instead as profoundly autistic.

Could all this explain why moderate autism seems to be so rare relative to profound and severe autism?

Indeed it could. Increased diagnosis of both high-functioning and profound autism relative to moderate autism could potentially flip the curve, raising the rates at both ends of the spectrum, but having no effects in the middle.

The middle of the spectrum, after all, is the home of the most quintessentially autistic individuals--those who most resemble the early cases on which Leo Kanner based his then-novel category "autism", and those who are least likely, since the onset of the DSM, to have ever been mistaken as falling into some other diagnostic category.

Unfortunately, I haven't been able to confirm (or disconfirm) this theory: the epidemiological data has a habit of either not disaggregating degrees of autism, or of conflating moderate autism either with severe autism ("moderate-to-severe" autism) or with "mild" autism ("moderate-to-mild" autism), or of being unclear or inconsistent about whether "high-functioning" autism includes moderate autism.

But for now at least, I'm left with the impression that the most quintessentially autistic individuals are, ironically, getting drowned out in an epidemic of diagnosis (overdiagnosis?) at both ends of the spectrum.

No comments:

Post a Comment