Sometimes it seems there are as many FC-defending tactics as there are FC proponents. One such tactic is to conflate facilitator influence with so-called “co-construction” or “negotiation” of meaning—the sort of thing that occurs between independently communicating conversational partners—as, for example, when one partner asks for clarification or completes the other partner’s sentence.

For example, Sonnenmeier (1993) compares conversational co-construction to the facilitator’s “stating of an entirely predicted word after a few letters have been selected,” as well as to the facilitator’s various “regulatory” functions:

“encouraging statements (e.g. ‘keep going’)”

“reminders to look at the keyboard”

“cues regarding written language conventions (e.g. ’you need a space after a word’; ’you can use a period if that's the end of your idea.’)”

“pulling the facilitated communicator's hand away from a wrong letter selection (which should only occur when a facilitated communicator has produced a string of letters that could never be understood)”

“interrupt perseverative selections.”

And Jaswal et al. (2020) compare interlocutors who help each other find words or complete each other’s sentences to the so-called “assistant” in their study, who:

sometimes redirected participants who seemed to lose their train of thought

requested clarification

interrupted, and said aloud a word before the participant finished spelling it

More recently, Nicoli et al. (2023), as I noted in my recent post, propose that the most likely effects of the facilitator’s touch on the FCed person’s typing” is a “co-creation” process that is analogous to someone who helps a mobility-impaired person walk. They don’t bother fleshing this out further or explaining how this kind of assistance in any way resembles co-construction/meaning negotiation in everyday conversation.

Returning momentarily to Sonnenmeier (1993), she, incidentally, also engages in another common pro-FC ploy: equating FC with AAC. Most AAC promoters, of course, reject this comparison. On the other hand, they, too, invoke co-construction of meaning (see, e.g., Beukelman & Mirenda, 2005). Examples of co-construction cited in AAC use include:

Partner-assisted scanning, in which the assisting partner moves through a series of items (e.g., letters, words, or pictures) and waits for a signal from the AAC using partner, which indicates the latter’s selection. After each signal, the assistant adds the selected item to the developing message.

AAC-mediated language instruction, in which a teacher or therapist attempts to elicit responses, asks for clarification, repeats back selected items, and/or models appropriate vocabulary and grammar.

While there’s nothing wrong with these AAC-based conceptions of co-construction/negotiation of meaning, they are specific to either to AAC or to speech-language therapy; they are not characteristic of independent, everyday conversation outside of instructional settings.

There is a problem, however, with the attempts by FC proponents to equate the co-construction/negotiation that occurs in everyday conversation with facilitator influence and facilitator prompting.

The co-construction/negotiation of meaning in everyday conversation takes several forms. One is “completion”: that’s when people complete each other’s sentences or suggest words when the other person is having trouble thinking of them or is otherwise distracted:

A: No matter what answer you give, you’re screwed. It’s like a…

B: Like a Catch 22 situation.

A: Yes, exactly.

As we’ve seen, FC-proponents have compared situations like this to cases where the facilitator says a word out loud before the facilitated person finishes typing it. But as those of us who’ve watched scores of FC videos can tell you, there’s one key thing that’s missing: the equivalent of A’s “Yes, thank you.” The facilitator does not seek confirmation from the facilitated person that he’s guessed the right word, nor does the latter provide such a confirmation. The guessed word serves as an instrument of message control, not of message assistance and message confirmation.

Another element of everyday message co-construction is “expansion.” This occurs when one person elaborates on another person’s message:

A: Last year we went to the Mütter Museum.

B: You and your students.

A: That’s right.

Once again, a crucial part of the co-construction process is the first speaker’s confirmation that his partner’s elaboration was accurate.

Other elements of co-construction involve requests for clarification, which also involve a confirming reply:

A: Where did he go?

B: Are you asking about Mark?

A: Yes.

One sort of co-construction is less visible and doesn’t necessarily lead to a process of clarification and confirmation: the listener’s interpretation of the speaker’s words. Many words mean different things in different contexts, especially pronouns like “he”; many sentences mean different things in different contexts, depending on how literally things are taken. Even a simple sentence like “It’s cold in here” can mean anything from a literal comment about the temperature to a request that someone close the window to an observation about an unfriendly social ambiance.

It’s worth adding that everyday AAC-mediated conversations can also involve completion, elaboration, clarification, and interpretation.

But there are limits to how much co-construction/negotiation of meaning occurs in real-life conversation. Only sometimes do we finish each other’s sentences—and we do so mostly with those we know best. Only sometimes do we elaborate or ask for clarification. And most of the time when we interpret someone’s words in context—e.g., the meaning of “he” or of “It’s cold in here”—we’re not too far off. Usually, the context suffices. Finally, even if we’re wrong, the speaker’s intended message remains. It is still there in her words and it’s still there in her head. And if need be, she can keep reasserting it, perhaps with different words, until it gets across. Her words may change, but her message may remain the same.

The only situation in ordinary conversation where messages change and evolve, and where each person potentially makes an equal contribution to a given message, is when the interlocutors are, in fact, collaborating on a message or an understanding of a problem or situation. Most of the time, however, things are far less cooperative: first comes A’s message, then B’s message, then another message from A, and so on. Whoever the current speaker is owns the current message.

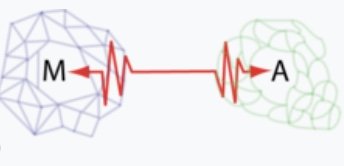

In FC, however, all the rigorous research shows that the speaker’s messages play no role at all in any so-called “co-construction.”

But even in a fantasized scenario in which the facilitator is somehow not controlling the messages, the sorts of “co-construction” that occur most frequently in FC bear no resemblance to co-construction in everyday communication. In addition to:

The lack of confirmation from the speaker when the facilitator says a word before the facilitated person finishes typing.

There’s:

The fact that a facilitator is not the same as a conversation partner. Despite recent rebrandings of FC in which facilitators are now “communication partners” or “co-communicators,” the facilitated person is not exclusively conversing with their facilitator. In Youtube videos, for example, they’re typically addressing interviewers or audiences.

The lack of any resemblance between the facilitator’s activities and instances of completion, elaboration, clarification, and interpretation in everyday conversation.

Indeed, none of these routine facilitator behaviors:

holding the facilitated person’s wrist or shoulder

pulling the person’s hand back from the keyboard

holding up the letterboard and shifting it around

whisking away the letterboard saying “keep going” when the person’s finger is not yet at the target letter

saying “right next door” when the person’s finger is one letter away from the target letter

saying “what makes sense” when the person is about to select the wrong letter

….have anything in common with the kinds of exchanges that occasionally occur in authentic communication:

A: No matter what answer you give, you’re screwed. It’s like a…

B: Like a Catch 22 situation.

A: Yes, exactly.

or:

A: Last year we went to the Mütter Museum

B: You and your students.

A: That’s right.

or:

A: Where did he go?

B: Are you asking about Mark?

A: Yes.

“Yes.” The independent word that confirms the message—so important in authentic communication, and so egregiously and pervasively absent in FC.

REFERENCES

Beukelman, D. R. & Mirenda, P. (2005). Augmentative & Alternative Communication: Supporting Children & Adults With Complex Communication Needs. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company.

Jaswal, V. K., Wayne, A., and Golino, H. (2020). Eye-tracking reveals agency in assisted autistic communication. Scientific Reports. 10:7882. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64553-9

Nicoli G, Pavon G, Grayson A, Emerson A and Mitra S (2023) Touch may reduce cognitive load during assisted typing by individuals with developmental disabilities. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience 17:1181025. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2023.1181025

Solomon-Rice, P. & Soto, G. Co-Construction as a Facilitative Factor in Supporting the Personal Narratives of Children Who Use Augmentative and Alternative Communication. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 32(2), https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740109354776

Sonnenmeier, R. (1993). Co-construction of Messages during Facilitated Communication Facilitated Communication Digest 1(2), [pp. 7-9]

No comments:

Post a Comment