(Cross-posted at FacilitatedCommunication.org).

When you write general guidelines, you need to make clear not just what you’re saying, but what you’re not saying. And to figure out which things, of all the things you’re not saying, you most need to emphasize as things you’re not saying, you need to take a look at who is likely—unwittingly or deliberately—to misinterpret what you’re saying, and in what ways.

In a 2021 article for the Brookings Institute, for example, education scholar Tom Loveless writes about how California’s 1987 English language arts framework got hijacked by the Whole Language movement, an ineffective, non-evidence-based mode of reading instruction that is responsible for much of America’s ongoing reading crisis:

The document did not mention whole language reading instruction, but true believers in that approach put their stamp on the state’s policies during implementation.

More recently, as Loveless reports, the equivocal writing in the 2010 Common Core standards, which aimed at a balance between Whole Language and traditional phonics, has resulted in something similar. In reality, there is no balance: non-phonics-based approaches (most especially the misnamed “Balanced Literacy,” with its “Three Cueing System”) continue to dominate reading instruction.

Here’s the takeaway: if governments want evidence-based reading instruction to predominate, their education standards need to explicitly state which types of reading instruction aren’t evidence-based.

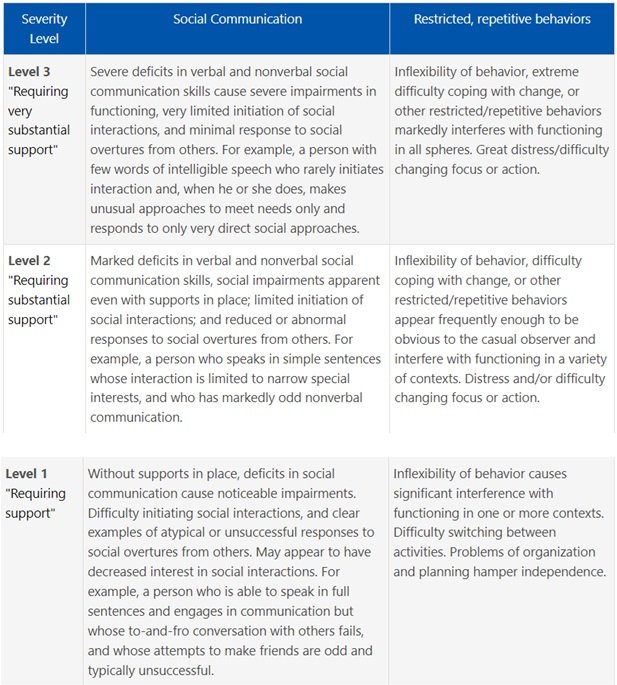

Switching gears rather dramatically, a similar lesson applies to the DSM-5 criteria for autism. One of the most controversial changes in the DSM-5 was its elimination of Asperger’s. Asperger’s, the mildest form of autism, is now folded into what was now a three-tiered “Autism Spectrum Disorder.” The problem lies in how the DSM has defined those tiers, or levels:

Level 1: “requires support”

Level 2: “requires substantial support”

Level 3: “requires very substantial support.”

Only in the fine print do we learn about the nature and purview of this support:

As is evident if you read past the first column, Level 1-3 support needs are defined, not in terms of the general requirements of daily living (organization, self-care, emotional regulation, and so on), but in terms of the two core symptom categories of autism: social communication deficits and restricted, repetitive behaviors. The levels, moreover, are a function of symptom severity.

For social communication/social interaction, for example, we have:

Level 3: “severe deficits in verbal and nonverbal social communication”; “very limited initiation of social interactions”; and “minimal responses to social overtures from others.”

Level 2: “marked deficits in verbal and nonverbal social communication”; “limited initiation of social interactions”; and “reduced or abnormal responses to social overtures from others.”

Level 1: mere “deficits in social communication”; “difficulty initiating social interactions”; and apparently “decreased interest in social interactions.”

[Emphasis mine]

And for restrictive/repetitive behaviors we have, among other things:

Level 3: “extreme difficulty coping with change” that “markedly interferes with functioning in all spheres”; and “great distress/difficulty changing focus or action.”

Level 2: “difficulty coping with change” that “interfere with functioning in a variety of contexts”; “distress and/or difficulty changing focus or action.”

Level 1: “difficulty switching between activities.”

The problem with this presentation is that, unless you read the fine print, it’s natural to assume that “support needs” means something much broader; that it includes support for any kind of need that might arise in the course of daily life—supports that might vary from day to day and from situation to situation. Supports for staying organized and keeping track of your things; for completing your assignments; for difficulties with emotional self-regulation; for fatigue and a need for frequent breaks. Support needs, in other words, that may be only indirectly or tangentially related to being autistic.

Because the DSM specifies the precise characteristics of autism support needs only in its fine print and doesn’t say explicitly what isn’t included as support needs, this much broader interpretation is precisely what some outspoken self-advocates have slapped onto it.

Some self-advocates, for example, have characterized themselves as having high support needs because of organizational challenges, sensory sensitivities, anxiety, exhaustion after social events, and/or occasional meltdowns. Indeed, according to the Autism Self-Advocacy Network, “Support needs are just things autistic people need help with.”

But here’s the issue. Some of those who are diagnosed as Level 2 or 3 based on more severe core autism symptoms may actually have less anxiety and/or fewer organizational challenges and/or fewer issues with sensory fatigue than some of those who are diagnosed as Level 1, at least at certain times and/or in certain situations. This broadening of support needs beyond what the DSM actually specifies, therefore, both fuzzes up and twists around the autism spectrum.

Imagine a highly verbal individual who might once have been diagnosed with Asperger’s and who views herself as highly anxious or disorganized or easily overloaded with sensory stimuli—especially, say, in large social gatherings or at the end of a long day. This person can now claim to be "as autistic" as a nonverbal individual with profound challenges in social awareness and social reciprocity that affect him every moment of every day. Highly verbal but sometimes overwhelmed individuals who identify as autistic can now claim they have the standing to speak on behalf of their nonverbal counterparts. Finally, FC proponents can now claim that Level 3 autism doesn’t rule out linguistic sophistication, whether in those who are verbal but anxious and overwhelmed, or in non-to-minimal speakers—at least when those non-to-minimal speakers point to letters on held-up communication boards.

Communication boards, coincidentally or not so coincidentally, figure prominently in my final example of guidelines that aren’t sufficiently clear on what they’re not saying. These guidelines come in the form of two documents: a “Dear Colleague” letter from the U.S. Department of Education regarding the need for assistive technology (AT) in special education, and an accompanying document entitled “Myths and Facts Surrounding Assistive Technology Devices.” Both of these went out on January 22nd of this year. The letter discusses the need for “AT devices and services for meaningful access and engagement in education” and adds that:

The use of AT devices and services is critically important for many children with disabilities as it can greatly improve their educational experience, improve their educational and post-school outcomes, and help develop important skills and abilities. These devices and services must be available, accessible, and appropriate for children with disabilities and their families. We all have a role to play in ensuring access to necessary AT devices and services for children with disabilities. Consider these examples of AT devices for children with a variety of disabilities.

The letter proceeds to list four categories of AT devices, one of which encompasses augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) devices. These are described simply as devices “to assist children with disabilities to communicate with teachers, peers, and their families.” The letter does not cite specific examples of what AAC devices are, let alone what they aren’t. Nor does the accompanying document, “Myths and Facts Surrounding Assistive Technology Devices.” But “Myths and Facts” does elaborate more on the larger category of AT devices, and here’s where the term “communication board” shows up:

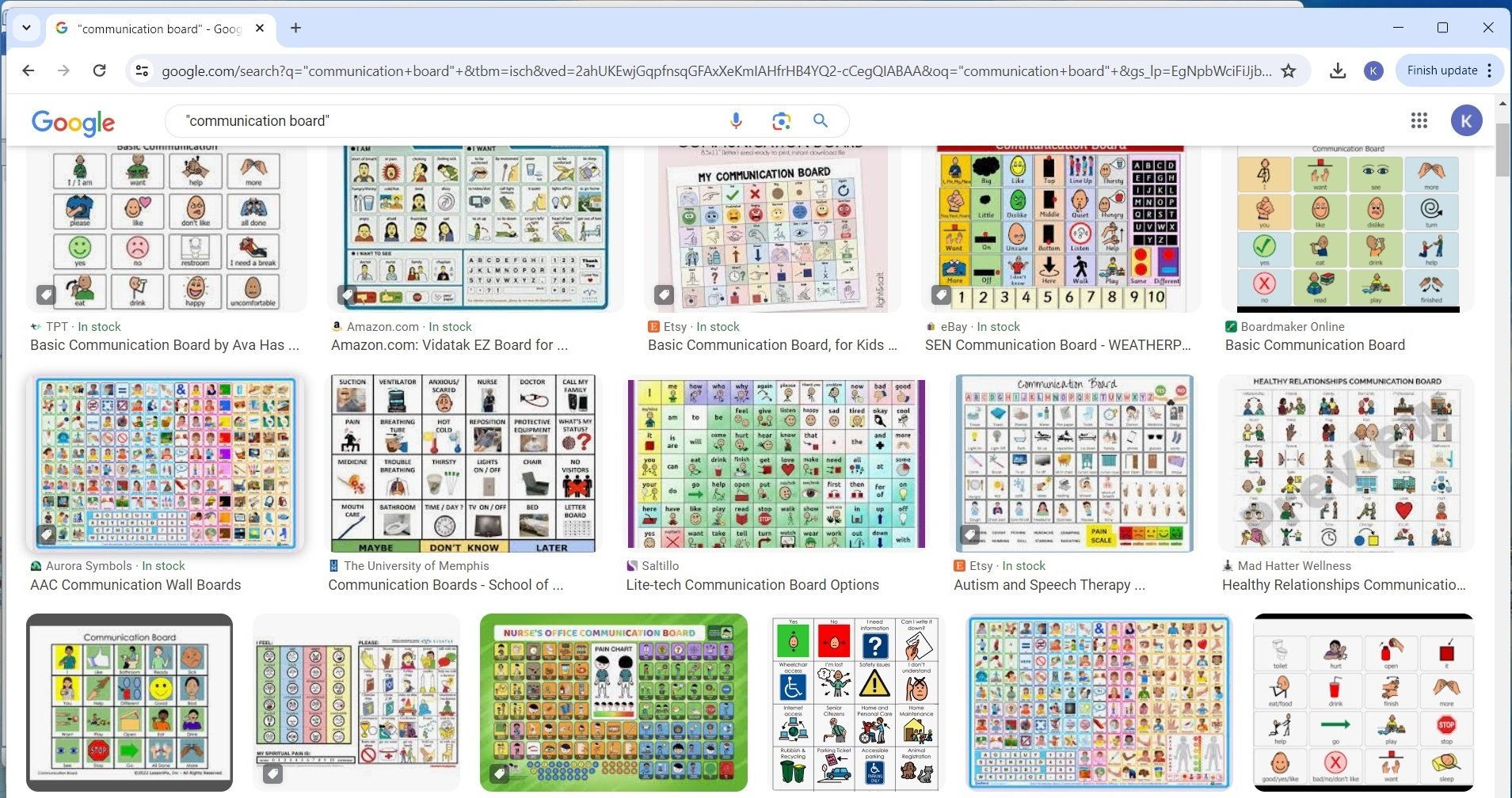

Any item, piece of equipment, or product system, whether acquired commercially off the shelf, modified, or customized, that is used to increase, maintain, or improve the functional capabilities of a child with a disability.39 Examples of AT include screen readers, adapted daily living devices (e.g., a toothbrush holder), and communication boards.

Unfortunately, however, “communication board” is ambiguous. If you look it up on Google Images, you see:

So far so good: these are all examples of evidence-based AAC devices that can rest on stationary surfaces and that allow users to independently communicate their own authentic messages by pointing to pictures, icons, or words.

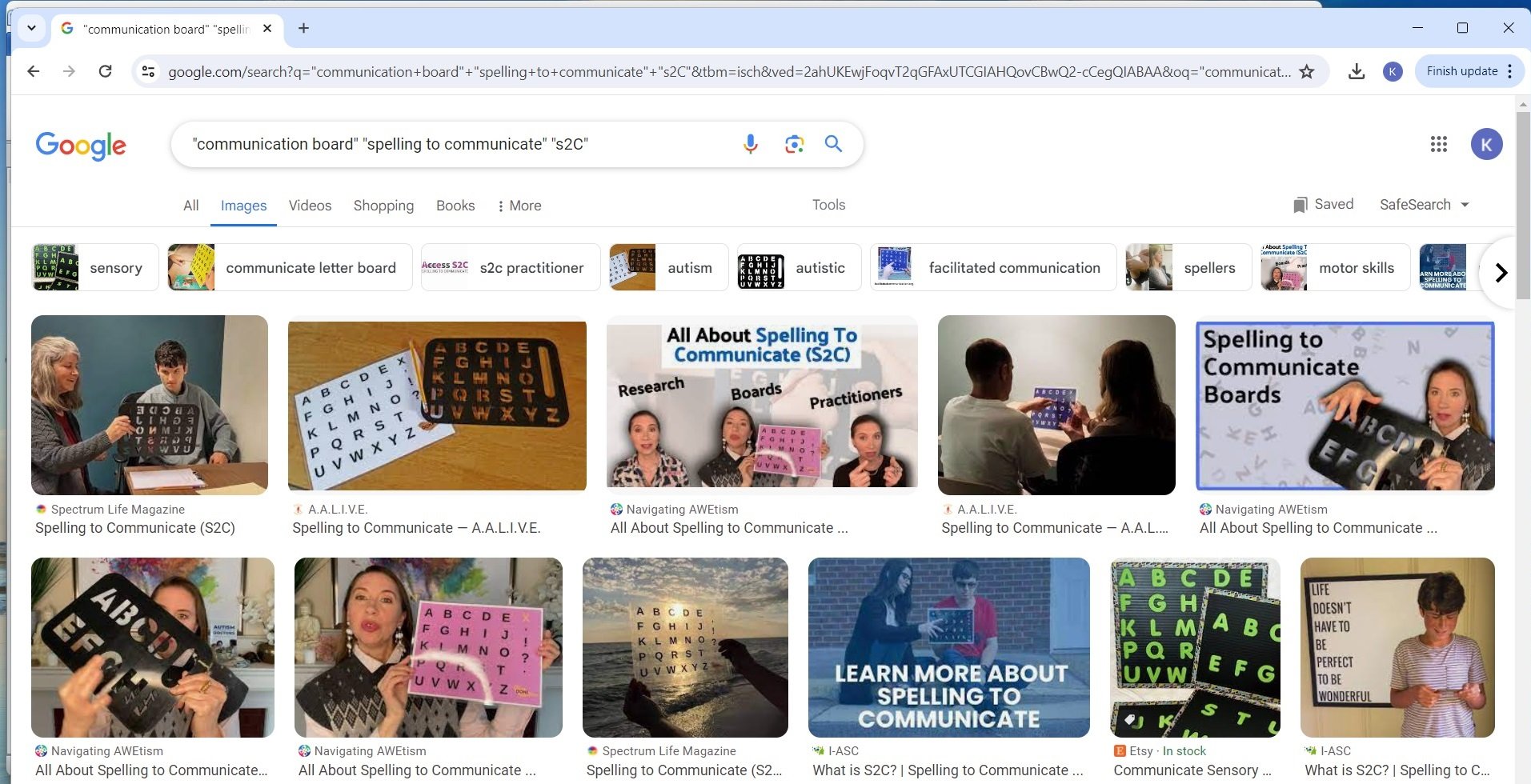

But if you add the search terms “Spelling to Communicate” and “S2C” to the “communication board” search, here’s what you get:

Suddenly we see the familiar held-up letterboards of S2C.

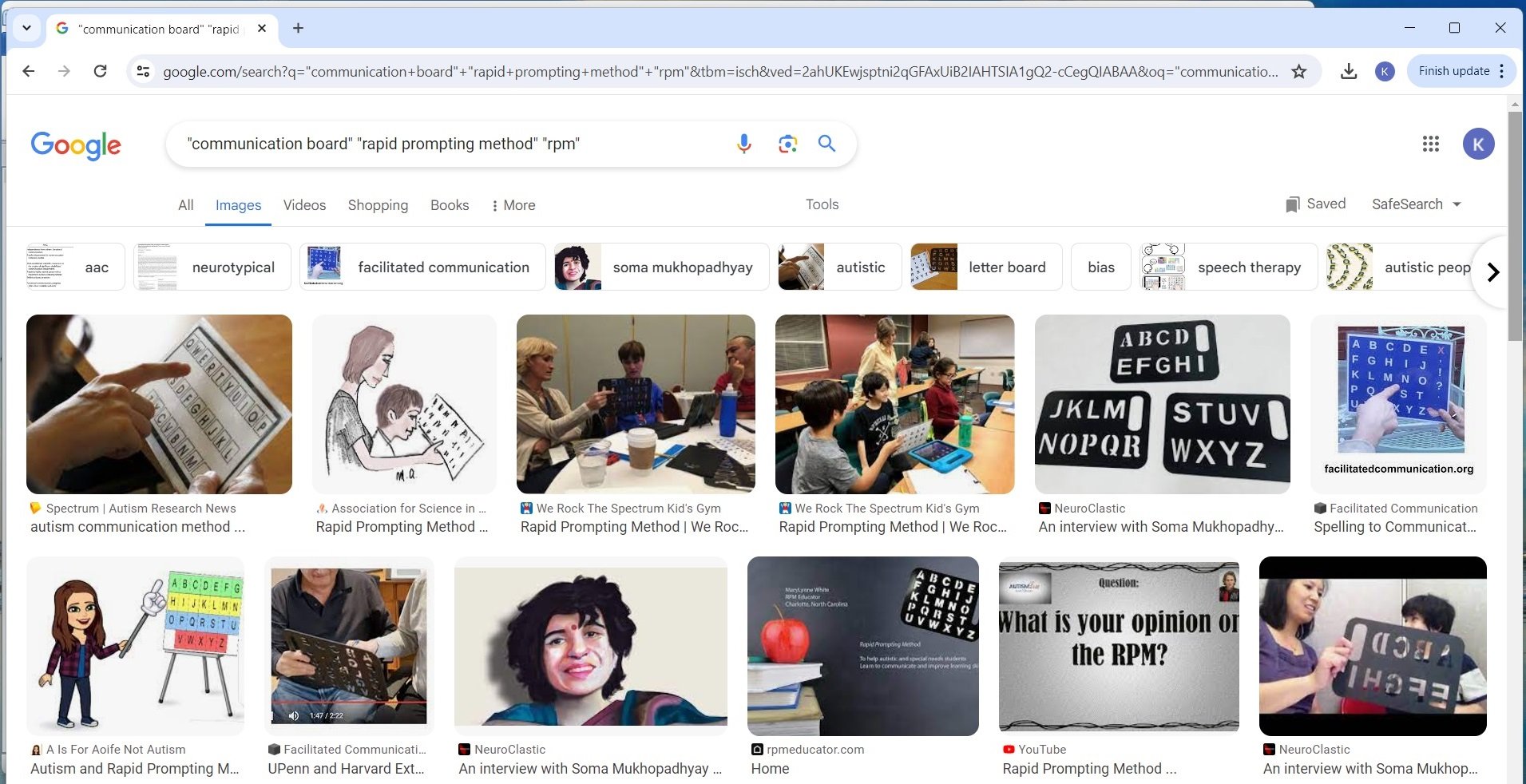

And if you add the search terms “Rapid Prompting Method” and “RPM” to the “communication board” search, you get something similar:

That’s because advocates of the variants of facilitated communication known as RPM (Rapid Prompting Method) and S2C (Spelling to Communicate) regularly use the term “communication board” for the letterboards that facilitators hold up to the index fingers of their non-speaking, Level 3 autistic clients.

So the U.S. Department of Education, by failing to specify which sorts of devices are and are not legitimate AAC devices, and by inserting the word “communication board” into its supporting document, provides an opening for supporters of RPM and S2C to claim that the U.S. government is calling for the use of RPM and S2C in schools.

And guess what? Just three days after the release of the Department of Education documents, the disability news journal Disability Scoop released an article entitled “Ed Department Warns Schools Not To Overlook Assistive Technology In IEPs” which opens as follows:

It’s hard to read the caption below the picture, but this is its first sentence: “Mitchell Robins, right, who has autism, points to letters to form words that therapist Anthony Bartell can write down to draft a blog post.”

The article makes no mention of S2C, RPM, or communication boards, and it only mentions AAC in the abstract. Those in the know, however, will instantly recognize in the caption and accompanying image all the tell-tale signs of S2C or RPM, and, in case there’s any doubt left, a quick Google search confirms that RPM is the methodology to which the pictured individual is being subjected.

In faulting the U.S. government and the DSM for being insufficiently clear about what they’re ruling out—whether it’s the Three Cueing System, a generic notion of support needs, and/or all variants of facilitated communication, hijacking all as these variants are of authentic communication—I’m assuming, of course, that the lack of clarity was inadvertent. But in the last case, the rapidity with which the release of the government documents gave rise to a celebratory article showcasing an RPM user (albeit while abstaining from all references to RPM or any other form of facilitated communication)—well, that one has me wondering.

Given how cozy certain sectors of the U.S. government have gotten with the FC lobby (see also the platforming of FC last year by the National Institutes of Health at the National Institute of Deafness and Communication Disorders webinar on nonverbal individuals with autism, and the inclusion of facilitated individuals as members of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Inter-Autism Coordinating Committee), I can’t help but wonder if the inclusion of the word “communication board” in the U.S. Department of Education’s “Myths and Facts Surrounding Assistive Technology Devices” was somehow, shall we say, strategic.

No comments:

Post a Comment