(Cross-posted at FacilitatedCommunication.org).

Reading up on another autism pseudoscience, “gestalt language processing,” has taken me to some early work on echolalia by Barry Prizant. Most of this work isn’t accessible through any of the three university libraries I have access to, so Prizant has done me a big favor by making it available on his website.

As I’ll discuss below, the presence on BarryPrizant.com of Prizant’s work on echolalia is actually rather surprising. That’s because of Prizant’s current support for the variant of FC known as “Spelling to Communicate,” or S2C.

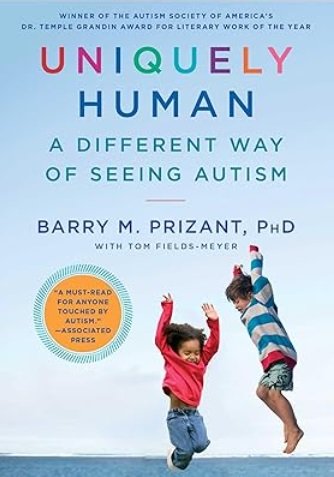

Signs of Prizant’s support for S2C were evident at least by 2015, with the first edition of his book, Uniquely Human. I discussed this book three years ago in a blog post entitled Uniquely Human: Laying the groundwork for belief in FC, and two years ago, Prizant stumbled upon my post and left this comment:

So who are you? At least clearly a died-in-the wool [sic], Lovaasian/Skinnerian kool-aid drinker. Why don't you ask me about what you say directly rather than cowardly taking pot shots, as is so common amongst so many ABA folks. I just ran across this joke of an analysis, and your comments and false assumptions are laughable. Dr. Barry Prizant

It wasn’t clear to me what I had gotten wrong. My discussion centered on cases where the facilitated person repeats words that are at odds with the words that are being facilitated out of them. I cited the infamous No More No More scene from the film The Reason I Jump, in which the movie’s voiceover, quoting statements attributed to a facilitated non-speaking autistic individual by the name of Naoki Higashida, explicitly dismisses the clearly intentional, echoic protests (“No more! No more!”) of the person being subjected to the S2C variant of FC, who appears eager to stop pointing to the letterboard and get out of the sun, which is clearly in her eyes.

Was I mistaken in saying that Prizant supported FC, which, I argued, contradicted what he’d said about echolalia? Or was I wrong about what he’d said about echolalia?

Prizant’s “Uniquely Human Podcast” has clarified things for me. At least four of its episodes (16, 35, 86, and 101) promote and platform S2C, and in the most recent one Prizant brings up echolalia. He does so explicitly in response to his critics, faulting us for being unaware that his earlier research found forms of echolalia that “were highly automatic and not intentional” and for having “no understanding of the continuum between automatic and intentional.”

The odd thing, however, is that the Uniquely Human book, in both its 2015 edition and the expanded 2022 edition, says that

[M]ost of the time, with careful listening and a bit of detective work, it becomes clear that the child is communicating—in the child’s own unique way.

Indeed, the articles that Prizant is best known for, those echolalia articles from the early 1980s, argue against the then-prevailing sentiment among autism experts that echolalia is primarily reflexive and meaningless. In his 1980s articles, Prizant identified eight interactive/communicative uses of echolalia that had previously gone unrecognized. These include two categories into which “No More! No More!” could easily fall: “requests” and “protests”.

Several decades later in Uniquely Human, Prizant alludes to a type of echolalia that appears nowhere in his earlier studies: “unreliable forms of echolalia.” While he does not define it, the name suggests that Prizant considers it a subtype of the “unreliable speech” that he and other S2C proponents claim is involved whenever what’s spoken conflicts with what’s typed. According to S2C proponents, whenever there’s a conflict between speech and S2C-generated text, we should assume that the latter is what the person actually intends to communicate—just as The Reason I Jump’s voiceover advises. No matter that S2C-generated text is highly susceptible to facilitator control, while speech is relatively immune—except in this fictional scene from the movie Being John Malkovich, whose patent absurdity makes it the exception that proves the rule. And no matter, moreover, that S2C proponents steadfastly refuse to conduct the sorts of rigorous message-passing tests that would establish whether a facilitator is controlling the S2Ced individual.

Given all this, what’s surprising about the presence on Prizant’s website of his earlier works is that some of what’s in them adds to the evidence against the validity of S2C.

First, while allowing that some echolalia can be automatic, the greatest emphasis of the 1980s version of Prizant, by far, is on echolalia as communicative. Indeed, Prizant and his co-authors found that the majority of the echolalia they observed was interactive and/or communicative (Prizant & Duchan, 1981; Prizant & Rydell, 1984). Prizant stresses how “Until recently, the predominant position was that echoic utterances are produced automatically with little or no communicative intent” (Prizant, 1983). And he underscores the importance of considering broader context and consulting caregivers to determine whether echolalia that might appear meaningless might in fact be meaningful (Schuler & Prizant, 1985). It’s hard to believe, therefore, that the Prizant of the 1980s would have thought that a contradiction or incompatibility between repeated speech (e.g., “No more! No more!”) and S2C-generated text (“We could finally tell each other we really felt”) was sufficient grounds for dismissing the former as meaningless and automatic.

Second, the Prizant of the 1980s found automatic echolalia to be characteristic of the “lowest functioning group of verbal autistic children, who remain echolalic for extended periods of time.” (Prizant, 1983). Prizant attributed the absence of “instances of more automatic and meaningless echoing” in earlier accounts of autism to “the sample of autistic individuals described, which did not include the more severely retarded.” (Schuler & Prizant, 1985). Reflexive echolalia, Prizant proposed, co-occurs with immature language and brain development (Schuler & Prizant, 1985). All this puts the Prizant of the 2000s in a bind with respect to the speech-to-typing conflict in S2C. If S2C is valid, then any speech at odds with the S2Ced messages must be reflexive; but if that speech is reflexive, the child is likely to be too low functioning to be the author of the S2Ced output.

Third, and perhaps most problematic for the Prizant of the 2000s, the Prizant of the 1980s attributed echolalia to “abilities in motor ability and rote memory which exceed linguistic comprehension and productive linguistic abilities.” (Prizant, 1983). In highlighting the differences between autistic echolalia and echolalia in typically developing children, he writes:

In contrast to more advanced object cognition… and relatively normal, even superior, perceptual-motor and memory skills, conceptual limitations in social cognition and related areas appear to be the core of the autistic syndrome. This discrepancy explains some aspects of autistic echoing as preintentional communication patterns are coupled with normal, relatively sophisticated speech imitation and memory skills. (Schuler and Prizant, boldface mine).

In other words, echolalia—especially early, automatic, non-communicative echolalia—is, per Prizant, the result of superior sensorimotor skills and limitations in social cognition. This is the exact opposite of what, some four decades later, he claims is going on in S2C. In S2C, according to not just Prizant but all S2C proponents, S2Ced individuals have deficits in sensorimotor function and intact or superior social cognition. Indeed, this is their basis for their claims that an S2Ced person’s speech is unintentional, non-communicative, and, in some cases, merely reflexive echolalia—at least whenever it’s at odds with what the person types.

What do we make of Prizant’s 180-degree turn?

Prizant’s early claims were based on objective observations of behavioral interactions; it’s unclear where his current claims are coming from. The most obvious explanation is that Prizant has fallen for naïve realism: the seeing-is-believing fallacy that leads naïve observers, including some autism experts with degrees in psychology, to think that S2C is real because it looks real to them. Indeed, it looks real to me is more or less what Prizant claimed in his letter to the American Speech-Language Hearing Association (ASHA) asking ASHA to retract its position statement against S2C and RPM (the FC variant from which S2C descended).

Prizant’s website contains no retractions of anything of his earlier positions. Instead, the commentary on the download page for the echolalia articles respects the spirit of this early work:

In our social-pragmatic research using early video analysis of echolalia used in natural activities, we were able to document that echolalia served a variety of functions for children.

And:

The following articles and chapters reflected our efforts to look at echolalia from a developmental perspective, and eventually shifted the perspectives of echolalia as an undesirable behavior to a multi-faceted, developmental phenomenon.

Perhaps Prizant is hoping people won’t look too closely and notice how this four decades’ old work, which has withstood the test of time, has also laid some of the groundwork for disbelief in something that has failed/will fail the test of time: namely, FC/S2C.

REFERENCES

Prizant, B. (1983). Language acquisition and communicative behavior in autism: Toward an understanding of the ‘whole’ of it. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 48, 296–307. https://doi.org/10.1044/jshd.4803.

Prizant, B. M., & Duchan, J. F. (1981). The functions of immediate echolalia in autistic children. The Journal of speech and hearing disorders, 46(3), 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1044/jshd.4603.241

Prizant, B., & Rydell, P. J. (1984). An analysis of the functions of delayed echolalia in autistic children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 27, 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1044/jshr. 2702.183

Schuler, A. L., & Prizant, B. M. (1985). Echolalia. In Communication problems in Autism (pp. 163–184). Springer.

No comments:

Post a Comment