(Cross-posted at FacilitatedCommunication.org).

A recent paper on language in autism has some interesting implications for facilitated communication and its variants.

But first, some context. Most studies of language skills in autistic individuals combine language production skills (mostly in spoken language) and comprehension skills (mostly of spoken language). When they examine distinctive facets of language like pronunciation, vocabulary, syntax, and pragmatics, they tend not to systematically disentangle comprehension from production. Vocabulary is often measured by comprehension: does the child point to, or look at, the picture of the “cup” when the word “cup” is spoken? Syntax tends to be measured by production: the child repeats a sentence or generates a sentence from a picture prompt, or observations are made of a child’s spoken language in real-life contexts. Pragmatics may be measured through judgments (or parent surveys) of the social appropriateness of the person’s utterances and/or the person’s judgments of the social appropriateness of hypothetical utterances by other people in different contexts.

Despite these common practices, separating comprehension from production and measuring a person’s comprehension of words, sentences, and socially embedded communications (directions, conversations, narratives) is arguably the best way to establish a person’s linguistic capabilities. That’s because comprehension precedes, and is a prerequisite for, meaningful speech. If one speaks without comprehension, that doesn’t really count as language; if one speaks hardly at all but understands a great deal, that does count as language—significant language.

Knowing a person’s language comprehension skills is crucial for making the following key determinations:

- how much they’re taking in when people talk to them

- how much information they’re able to learn through verbally presented material

- how much they understand of what they’re saying or typing when they speak or type

And here’s where the connection to FC comes in: a person’s typed-out messages cannot possibly be coming from that person if he or she doesn’t understand the words, phrases, syntax structures, and informational content that comprise those messages.

Then there’s the connection to autism: language comprehension difficulties have been found to be more essentially connected to autism than language production difficulties are. That’s because comprehension necessarily involves something that is inherently challenging in autism: turning into other people and getting inside their heads. To understand what a specific word refers to, or what an entire spoken or written message means, you need to figure out what the speaker/writer is referring to, and/or what their subtext is, and/or what their purpose is.

Few papers, as I said, have focused specifically on comprehension in autism, but a new paper has just come out that helps to fill this gap: Vyshedskiy et al. (2024).

On one hand, Vyshedskiy et al.’s language comprehension data doesn’t come from the most reliable source: they used parent surveys rather than professional assessments. On the other hand, their sample was huge and broad: 31,845 autistic individuals from 4 to 21 years of age.

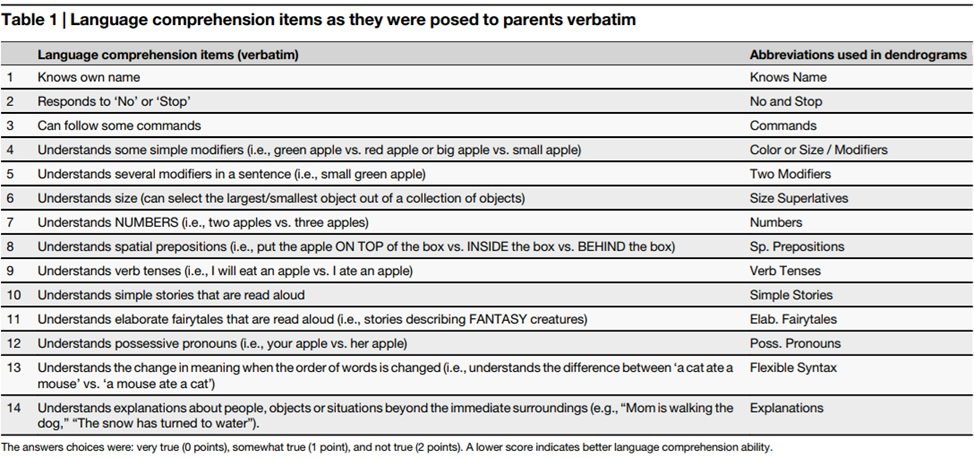

To measure language comprehension, they used this:

The first nine of these questions—from “knows own name” to “understands verb tenses (i.e. I will eat an apple vs. I ate an apple”)—look straightforward and specific enough to be amenable to objective answers. So do questions 12 and 13. In some cases, the parent might not know the answer offhand, but the questions make it clear how to prompt the child to figure it out.

Only questions 10, 11, and 14 are potentially problematic, focusing on linguistic phenomena—stories and explanations—where it may be easy (and even tempting) to read in more comprehension than really is there.

To measure factors other than comprehension—including expressive language, sociability, and sensory sensitivities—the authors used something called the “ATEC questionnaire.” (They state that “Various studies confirmed validity and reliability of ATEC”).

As for the authors’ methodology, this was potentially more objective than what’s possible with smaller data sets. Rather than trying to make the data fit pre-existing assumptions, they used an automated, unsupervised cluster analysis to determine which non-linguistic factors correlated with which comprehension profiles. And their results, as it turns out, are not particularly convenient for FC proponents.

Their cluster analysis identified three distinct levels of language comprehension:

- individuals in the command-language-phenotype, who were limited to comprehension of simple commands (40% of the sample)

- individuals in the modifier-language-phenotype, who could also comprehend color, size, and number modifiers (43% of the sample)

- individuals in the syntactic language-phenotype, who could also comprehend spatial prepositions, verb tenses, flexible syntax, possessive pronouns, and complex narratives. (17% of the sample)

And here’s what the cluster analysis showed:

Participant clusters displayed statistically significant differences in properties that were not used for clustering, such as expressive language, sociability, sensory awareness, and health… demonstrating that language comprehension phenotypes are associated with symptom severity in individuals with ASD. [Boldface mine].

In particular, the authors report:

- The syntactic language phenotype had the greatest proportion of individuals characterized by parents as having mild ASD and the lowest proportion of individuals with severe ASD.

- The command language phenotype had the greatest proportion of individuals characterized by parents as having severe ASD and the lowest proportion of individuals with mild ASD.

Since those most likely to be subjected to FC are those with the most severe autism symptomology, this finding adds to the mounting evidence that those subjected to FC do not have the comprehension skills to author the linguistically sophisticated messages that are attributed to them.

In addition, the authors find the following connection to expressive language skills:

91% of children in the command language phenotype were nonverbal or minimally verbal, compared to 68% in the modifier language phenotype, and 33% in the syntactic language phenotype.

Since those most likely to be subjected to FC are minimally verbal individuals, this finding also adds to the mounting evidence against the purported authorship skills of those subjected to FC.

But what about the finding that 33% of individuals in the highest comprehension group are minimally verbal?

It’s possible that some of those individuals fell into that cluster, in part, because their parents over-estimated their comprehension of stories and explanations—a possibility I suggested earlier. Intriguingly, however, this is not the first time evidence has emerged of a subset of minimally verbal individuals with relatively intact comprehension skills. About a year ago, I wrote a blog post that reported on a study presented at the 2023 INSAR conference—a study that has since been published (Chen et al., 2024).

Like Vyshedskiy et al., Chen et al. looked at comprehension. Their sample consisted of 1579 minimally speaking autistic children, and they found that:

- minimally speaking autistic children had much lower receptive language skills (comprehension skills) compared to their neurotypical peers

- this gap widened with age

- receptive language skills correlated with social skills (and thus with one component of autism severity)

And like Vyshedskiy et al., they found that there exists a subset of minimal speakers—about 25% of their sample—in which receptive language skills are relatively high relative to expressive skills (e.g., speaking skills). However, they also found that the receptive language skills even of this unusual subgroup

- are still lower than those of same-aged, non-autistic individuals

- are positively associated with motor skills.

That is, as Chen puts it in a video describing her findings:

[I]n this subgroup, motor skills emerge as the only significant factor predicting the discrepancies between receptive and expressive language [language comprehension and language production] above and beyond all other factors. And those with better motor skills are more likely to have much better receptive language than expressive language.

And this amounts to one more piece of evidence that those who are supposedly most in need of FC—i.e., because of their purported motor difficulties—also have the worst receptive language skills.

References:

Chen, Y., Siles, B., & Tager-Flusberg, H. (2024). Receptive language and receptive-expressive discrepancy in minimally verbal autistic children and adolescents. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 17(2), 381–394. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.3079

Vyshedskiy, A., Venkatesh, R. & Khokhlovich, E. (2024). Are there distinct levels of language comprehension in autistic individuals – cluster analysis. npj Mental Health Res 3, 19. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-024-00062-1

No comments:

Post a Comment